October Roundup

Dorothy Sayers on Marriage, Leithart on actually Biblical womanhood, God's Law as Commentary on Nature, an undiscovered Chopin Waltz

Photo by Georg Eiermann on Unsplash

My Writing

This month I published the second installment in my series looking at marriage metaphors in the Old Testament:

When the prophets use marriage imagery to describe Yahweh’s grief and anger over his people’s sin, and his desire to win them back, they do so within the parameters of this law. How can Yahweh take his people back again, if doing so would violate his own command concerning the return of the divorcee? Hosea shares many themes and affinities with Deuteronomy, so it is worth exploring how Hosea in particular picks up this puzzle.

Read the full piece here.

What I’m Reading

The Glory of Man

When I heard about this new work by Peter Leithart on the creation and nature of woman, I couldn’t get my credit card out fast enough. Leithart (who was my college theology professor) is always insightful and brings his immense knowledge of Scripture to bear on any question he tackles. In Glory of Man, Leithart looks at some historical misconceptions about womanhood and offers a robust answer.

This book was so thought-provoking that I might need to write my way through it. But by way of a brief overview, here are some highlights that I think are worth mentioning.

Leithart grounds sexual differences in the Trinity. He says,

Though difference and union within God isn’t sexual, it’s the uncreated pattern of which sexual difference and union is the image. The mysterious depths of human sexuality are divine depths. (38)

Many have tried unsuccessfully to ground gender relations in the Trinity. The primary mistake people make is to posit a hierarchy within the Trinity in order to explain an assumed hierarchy between man and woman. I’m not a theologian, so I could be wrong about this, but it seems to me that Leithart’s vision of seeing the Trinity as an “uncreated pattern” for sexual difference responsibly grounds anthropology in the Trinity while avoids the error of eternal subordinationism.

According to Leithart, here are some of the contours of this uncreated pattern:

1) “Because Triune love is the love who is the Spirit, the love of the Persons is erotic, not, as some suggest, merely philia or agape. The Persons desire one another, with infinite desire.” (37)

2) “The Triune Persons ‘fit’. The Father is capacious enough for the Son to abide “in” Him, and vice versa (John 14:10-11, 17:21). . . Their mutual eros is truly eros, truly longing, truly desire, yet it’s eternally fulfilled in infinite union and mutual indwelling.. Each makes room in Himself for each.” (37)

3) “The Trinity is fruitful. Through the Spirit who indwells Him, the Father generates His eternal Son. . . The Father is never barren, never unproductive, but eternally generative.” (37)

He goes on to also connect the nature of gender to the relationship between God and Nature and the relationship between heaven and earth, respectively. These are more common metaphors that can be found both historically and in recent evangelical discourse.

I find this multi-faceted approach refreshing. Somewhere along the line, Christians began restricting divine gender metaphors to only one: Man= Christ/God and Woman= Church/Creation. It’s not hard to see how this inevitably leads to enormous problems. It’s extremely bad for both men or woman to think that only men are “like” God. The solution is not to try to make God into a woman in order to even the playing field. Rather, we need to understand that whenever we describe God in gendered terms, we are simply using our knowledge of human nature to describe an eternal, genderless, God who is “without parts or passions.” We are like God, but God is not like us.

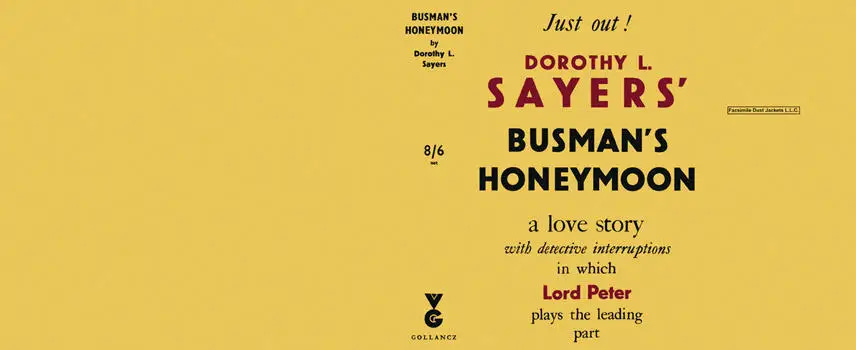

Busman’s Honeymoon

I am a huge Dorothy Sayers fan. Insightful, funny, and whip-smart, Sayers was also shockingly broad. She wrote detective mysteries, a treatise about the Trinity and creativity, a manifesto on womanhood, did a translation of Dante, and several plays. She wrestled deeply with many questions, not least was the problem of gender in modernity.

Busman’s Honeymoon (1937) is the final novel in the Harriet Vane + Peter Wimsey stories. In it, Harriet and Peter are finally married (after six novels of Harriet resisting Peter’s advances) and go off on their honeymoon. Predictably, they find a body on their honeymoon, and are thrown into solving a case while spending their first days together as husband and wife. I don’t think Busman’s Honeymoon is Sayers’ best novel, and I don’t know anyone who thinks so. It takes 100 pages for them to even discover the body, during which time there is more chimney-sweeping than belongs in any novel. But Busman’s Honeymoon novel is special for at least one important reason. If Gaudy Night is the ultimate exploration of modern women’s work, vocation, and romance, Busman’s Honeymoon is an exploration of these themes within marriage.

What happens to the relationship between a woman and her work when she gets married? What is supposed to happen? Does one vocation supersede another, or is it possible to weave vocations together as different expressions of your humanity? Sayers is intensely interested in these questions.

Wimsey is a private detective and Vane is a mystery novel writer. Each bring a unique but overlapping set of knowledge and instincts to bear on the case. This is not the first case they have worked on together, but it is the first they have worked on while openly and honestly in love, and while married. Harriet consistently balks at any attempt to sentimentalize or trivialize their relationship. Reporters swarm to cover the story of the murder, and while they’re at it, they want a story on the “brassy career lady” who has married Lord Peter.

“About this writing story—can you give me anything exclusive on that? Your husband eager you should continue your professional career—that kind of thing? Doesn’t think women should be confined to domestic interests? Your looking forward to getting hints from his experience for use in your detective novels?”

“Oh, damn!” said Harriet. “Must you have the personal angle on everything? Well, I’m certainly going on writing, and he certainly doesn’t object—in fact, I think he entirely approves. But don’t make him say it with a proud and tender look, or anything sick-making, will you?”

One of Sayers’ life frustrations was the way women are assumed to be so different than men that they essentially have a different nature. Simply by doing the work she is suited for, Harriet Vane is considered by the reporters (and others) to be a kind of spectacle. This was one of the major themes of Sayers’ work, and it’s no wonder. Sayers was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford after they opened their doors to women. She made a name for herself as one of the great mystery novel writers of the 20th century when it was still new and suspect for a woman to be supporting herself with her own work. Busman’s Honeymoon is an entertaining and insightful offering into the conversation about how vocation interacts with marriage, and the possibility of marriage between two people with the same vocation.

What I’ve been Thinking About

This past weekend, I had the pleasure of organizing the Davenant Institute’s first Convivium (Convivium: mini-conference but jolly) here in Raleigh. The topic was Theology and Law, looking specifically at historical theological insights that shed light on criminal justice. The topic is not one I know much about, but I always find Davenant’s Law Convivia extremely thought-provoking, and half the time I can’t help think I would have really thrived in Law if it had occurred to me to pursue.

One of the central questions we discussed was, what is the place of Scripture in determining just laws and policies in a secular system? This seems extremely timely as Christian nationalism increasingly becomes a catch-all phrase for any show of Christian conviction in public. It is not likely that a lawyer will find much traction to argue for a particular policy or case outcome based on a Bible verse.

A lot of the legal theory we take for granted was developed as legal theorists wrestled with gnarly passages that they understood could shed light on complex contemporary issues. They saw Scripture as completing the revelation that began when God spoke all of nature into being. Traditionally, nature was understood not as something totally “other” than God, something fallen and evil, but rather as God’s speech. God did not make everything in a haphazard, toss-about way, such that we need to ignore what we see around us in order to listen to God. Rather, everything we see and experience is part of God’s speech, including morality. God might have used a different color scheme or made gravity work differently, but he could not have created a world in which it was ethical to kill your parents or commit adultery. God’s character forms the boundaries for moral law.

So there’s a sense in which we can think of the Torah as being God’s commentary on nature. We all understand instinctively, because it is written on our hearts, that we owe our parents some debt of honor and gratitude. But God comments on this instinct with a fuller revelation: it is those who honor their parents who will prosper in the land.

As we consider which positive laws and policies would be just in our particular context, it would be good—essential even—to have the Torah and Gospels built into our minds through meditation and memorization. The 1970s-90s provided us with many well-intentioned but klutzy examples of Christian leaders trying to derive “principles” from Scripture. In theory, deriving principles from Scripture is exactly what we should be doing. But we go wrong when we try to pick up Old Testament case law and slap it onto contemporary situations. The point of the Law is to get to know how God thinks. If we are in the habit of thinking along with God, then we will have a chance at discerning what he thinks about a particular situation.

In other words, we should all spend considerably more time in Scriptural study, contemplation, and memorization.

Links

The Dead End of Political Misogyny in Compact, by Erika Bachiochi

The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval from Peco and Ruth Gaskovski

A newly discovered Chopin waltz!