November Roundup

Jeremiah's marriage metaphors, Jane Austen's virtue ethics, and are traditonal schools actually better for girls?

My Writing

This month I published the third installment in my “Yahweh’s Marriage” series about marriage metaphors in the Old Testament prophets. Here I looked at how Jeremiah picks up themes laid out in Hosea, and reworks them to fit Judah’s new situation.

Jeremiah saw the law governing divorcees in Deuteronomy 24:1-4 as a hindrance to the possible reunification of Yahweh with his people. In this case, Israel did not have a second husband, but she had many lovers in the false gods she worshiped.

For Jeremiah, if Israel were to marry Yahweh a second time, it would pollute the land and violate his own law. And yet, Jeremiah has read of the hope that Yahweh offered his people through the prophecies of Hosea, so he set about to discover how this happen.

Read the full article here.

My Speaking

Somehow I missed that the talk I gave on Jane Austen and virtue last year at Davenant’s Spring Convivium had been posted on their podcast feed.

Are Schools Better for Girls than Boys?

Recently I’ve been in lively conversation with at least two different friend groups about gender and education. The problem of the feminization of academia has been much discussed lately, as well as the question of why girls seem to be doing so much better in school than boys. Many argue that traditional school has been structured around girls’ needs and learning styles: sitting quietly, cooperating, being rewarded for obedience. Since girls are naturally more obedient, schools are better designed for their needs. In contrast, boys are naturally more physically active and agentic, and less inclined toward obedience, all traits that schools actively quash.

I think this argument is true as far as it goes, but I would add an important qualification: if traditional schools only encourage girls in their natural social and learning tendencies, then they are not growing them to maturity. It might be the case that girls are better suited to schools the way they are structured now, but does it follow that this is a good thing? What if an over-emphasis on obedience is actually preventing kids from learning how to think?

Traditional school rewards compliance and obedience. It should be obvious that obedience is good or bad depending on the situation. For girls to be constantly rewarded for obedience rather than agency, creativity, and independence of thought actually grows girls away from these essential virtues.

Boys may not be thriving in compliance-based education, but they often build a certain level of agency and independence simply because they get in trouble more frequently, which many boys in typical schools do. In contrast, we think girls are "doing well" because they are good at playing the game, getting good grades, etc. But are they building the intellectual virtues they need? Being able to jump through hoops is not the same as learning to think for yourself.

Obedience is an essential virtue for both men and women to cultivate. But I would argue that an over-emphasis on conformity and obedience produces managerial thinking and a lack of independent thought. These are not traits that belong to the feminine, but to the immature feminine. Effective education does not just accommodate, but also challenges our natural inclinations.

What I’m Reading

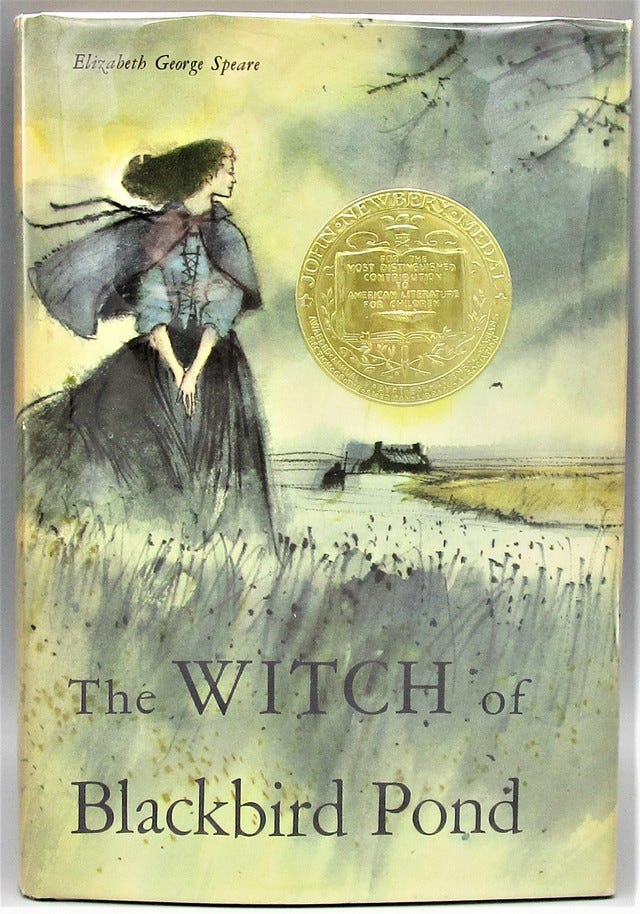

This month I re-read The Witch of Blackbird Pond, a book I have read at least 25 times. Aside from the Narnia books and The Lord of the Rings, The Witch of Blackbird Pond is probably the work of fiction that has shaped my imagination the most. And as I read it this past month, it struck me that Elizabeth George Speare explores many of the same issues I have been thinking about.

After the death of her grandfather, Kit Tyler, a wealthy orphan from Barbados, arrives on the doorstep of her aunt and uncle in Colonial Connecticut. As she slowly adapts to the austere ways of the Puritan community, she gains an appreciation and respect for a people who have survived and built a life in the face of great hardship. Her misadventures show the constant tension between our drive to fit into a community and our drive to be ourselves.

Speare explores the way communities can act as a swarm, forming collective intellectual judgments and prejudices that may or may not have anything to do with reality.1 The Salem witch trials are the perfect (disturbing) foil for this essential question. This also incidentally ties in my thoughts above on gender and education.

If we decided to be satisfied, as many philosophers and theologians throughout history were, with obedience as a “feminine” virtue, then the sort of group moral hysteria that is a witch hunt is precisely what we would expect to find. An over-emphasis on obedience combined with a lack of education creates precisely the sorts of women (or men) who lead and participate in swarms and mobs. The vindictive and superstitious women in Wethersfield who accused Hannah Tupper and Kit of witchcraft were uneducated, suspicious of book learning, overly conformist, and had lived a cramped and stationary life. In contrast, Kit had grown up reading, swimming, running free, and exposed to the world. Although she struggled to fit in in Wethersfield, she was better equipped to consider new ideas, form judgments, and correctly discern what was going on around her.

The happy ending Kit finds at the end of the novel is reminiscent of Austen’s ideal in Persuasion: a man and a woman carving out a life together that balances rootedness with mobility, tradition with openness, and that situates obedience in the full array of virtues that men and women must both cultivate.

Links

Reclaiming Time: Why Women Should Challenge the Productivity Industry

The Sacred Sounds of Hildegard of Bingen

Quotable

Two quotes this month, which I think make a nice pair:

Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin administered the next shock: “It troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn.” Was it a sense of things passing, even passing away, of wanting sunlight, cooling air, leaves erupting in color before crumpling to the ground? Lewis doesn’t say; but it is noteworthy that the minimal plot involves Squirrel Nutkin challenging Old Owl with a series of riddles, all left unsolved, evoking the mystery of existence, felt most keenly as dark and cold usurp sun and light.

From The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings, 42

Going through the shed door one morning, with her arms full of linens to spread on the grass, Kit halted, wary as always, at the sight of her uncle. He was standing not far from the house, looking out toward the river, his face half turned from her. He did not notice her. He simply stood, idle for one rare moment, staring at the golden fields. The flaming color was dimmed now. Great masses of curled brown leaves lay tangled in the dried grass, and the branches that thrust against the graying sky were almost bare. As Kit watched, her uncle bent slowly and scooped up a handful of brown dirt from the garden patch at his feet, and stood holding it with a curious reverence, as though it were some priceless substance. As it crumbled through his fingers his hand convulsed in a sudden passionate gesture. Kit backed through the door and closed it softly. She felt as though she had eavesdropped. When she had hated and feared her uncle for so long, why did it suddenly hurt to think of that lonely defiant figure in the garden?

From The Witch of Blackbird Pond, 147

This idea is also explored in this article on community and cognition in Pride and Prejudice.